The Broken Record

The year 2024 has ended, and once again, the temperature record has been broken. For the first time, we have surpassed the 1.5°C warming threshold compared to the pre-industrial period. What does this mean? Has the Paris Agreement's limit been breached? And is there still anything that can be done?

2024 was the hottest year in history. Again.

2023 was the hottest year before that, and before that, 2020, and then 2016. In the last decade, the record for the hottest year has been broken again and again. In fact, if you, your children, or your grandchildren are under the age of 20, they have lived through all of the hottest years since records began.

But now it’s official – the past year, 2024, was the hottest.

On one hand, extreme events are intensifying, and we are seeing the consequences of climate change unfold before our eyes – wildfires in California, floods in Spain, deadly storms in Mozambique, and terrifying cold snaps in the U.S. At the same time, there is greater recognition of the magnitude of the crisis – at least in some sectors – and ambitious plans are being written for mitigation (reducing greenhouse gas emissions) and adaptation (adjusting and preparing for the consequences of climate change).

What does it mean for us that temperature records are being broken again and again? Is all hope lost? What can be done? What is the role of technology in finding solutions, and of the world’s citizens? Are our experts on campus pessimistic or optimistic?

To answer these questions, we went in search of the latest data.

So the temperatures are rising, we’ve already said that.

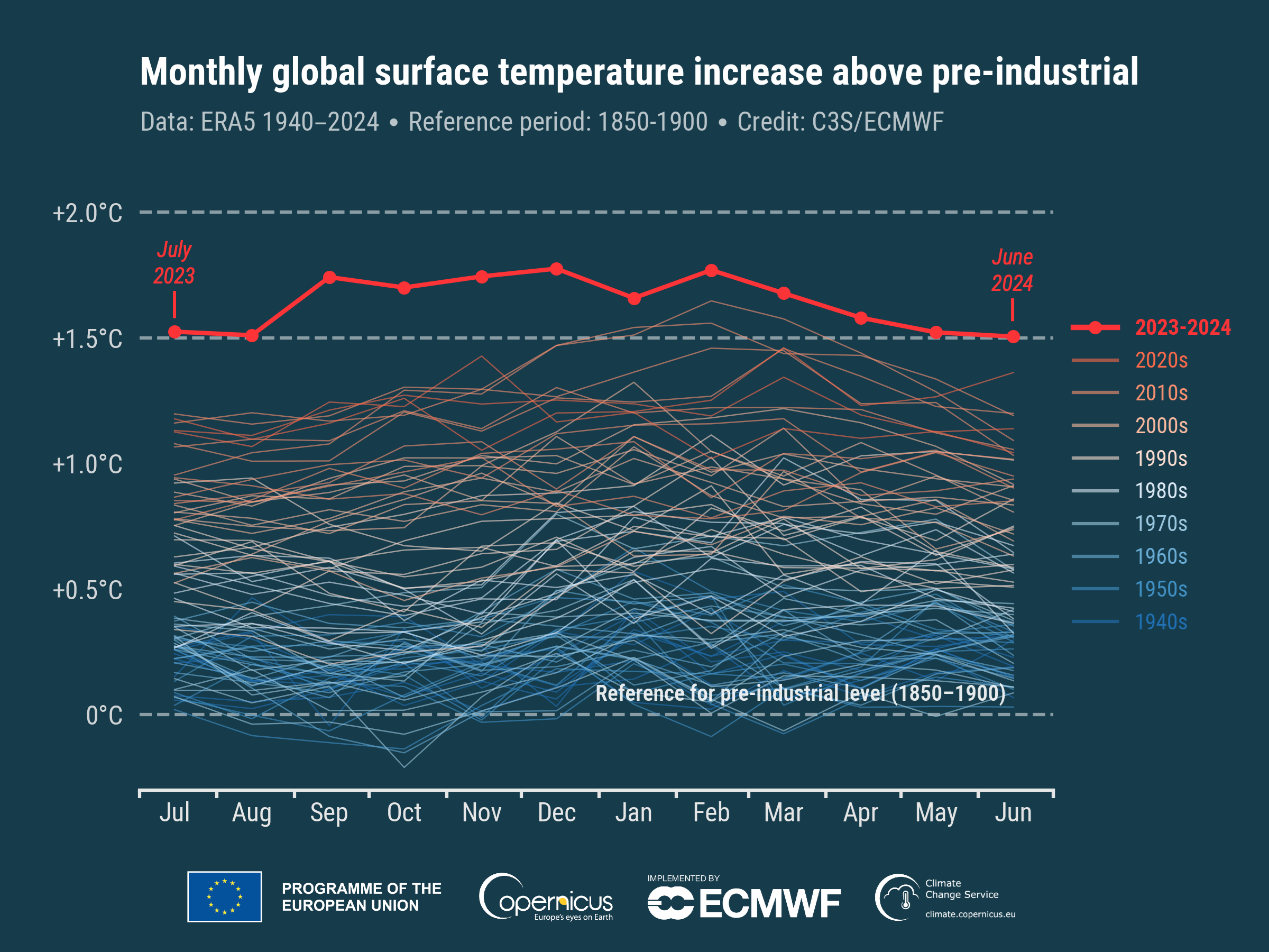

At a global level, we are trying to keep global warming below 1.5°C, otherwise we expect to have to deal with devastating consequences for the Earth's ecological, economic, and social systems. But from July 2023 to June 2024, every month exceeded the 1.5°C threshold. Does that mean we’ve already reached the threshold we wanted to avoid? Yes and no.

No, because when we talk about climate and average temperature, we never look at just one year; instead we refer to an average over 20-30 years, the timeframe that typically defines the climate.

At the same time, yes, because we are definitely on our way. If warming continues at this accelerated pace, we expect to reach the point where we cross that threshold in the early years of the next decade, just after 2030.

Average temperature anomaly (temperature relative to the pre-industrial period average – 1850-1900) from July 2023 to June 2024 compared to the temperatures of the preceding decades. Source: C3S / ECMWF

If there are hotter years and colder years, doesn’t that balance things out?

We look at the distribution of average global temperatures relative to the pre-industrial average, about 200 years ago, when fossil fuels – oil, coal, and natural gas – started to be burned at an increasing rate, raising greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. It’s clear that in the past we had both hot days and cold days relative to that pre-industrial average. However, since the 1980s, we have seen a clear shift in the entire distribution of averages, so now even the colder days are equivalent to what used to be the hottest average Earth temperature. In addition, the temperature distribution is becoming more and more extreme –the averages are changing but also the distribution between hotter and colder days is shifting, with more and more hot days and fewer and fewer cold days. In short, we’re heating up, and at an accelerating pace.

Graph of Average Global Temperature Distribution Relative to the Pre-Industrial Period. Source: ERAS, C3S/ECMWF

So yes, there is reason for concern. At this point, it's good to talk to experts in the field to hear whether they are concerned about the situation. We spoke to Prof. Colin Price from the School of the Environment and Earth Sciences, and head of PlanNet Zero, and Prof. Ruth Ronen, from the Department of Philosophy who also developed the TAU interdisciplinary course on "Climate Crisis and Sustainability"

"The main thing that worries me in light of the new record being broken," says Prof. Ruth Ronen, "is the gap between what science knows about the causes of warming and scientific forecasts for the future, and what the public has internalized. Despite the fact that the climate crisis is real and present in everyone's lives, the science dealing with the crisis remains 'expert science,' and the most serious and dangerous crisis in human history features relatively little in public discourse."

"My greatest concern," shares Prof. Colin Price, "is related to 'tipping points.' As temperatures rise, we’re getting closer to thresholds that, once crossed, we might not be able to reverse. The rising sea levels due to the melting of ice in Greenland and Antarctica are a perfect example – it will be nearly impossible to reduce sea levels again. The process of rebuilding ice takes tens of thousands of years, but we are witnessing melting that has taken just a few decades. Once coastal cities are flooded, we will either have to adapt by building defenses and dams or relocate to higher ground, which means significant migration. Another tipping point is the thawing of permafrost in high-latitude areas – Siberia, Canada, Alaska – the ground there contains large amounts of organic material, and thawing could lead to a massive release of greenhouse gases, including methane, a particularly powerful greenhouse gas. These additional greenhouse gases will be very difficult (and expensive) to remove from the atmosphere and could lead to accelerated warming."

Prof. Ruth Ronen, Department of Philosophy, Faculty of Humanities, Tel Aviv University

What do you think it’s important for the public to understand, when yet another temperature record is broken?

"It’s important for the public to understand the implications of a constant rise in average temperatures in terms of the human body’s survival and the overall social fabric," says Prof. Ruth Ronen. "For example, what happens to the body at high temperatures, and how heat affects behavior, human relations, and so on."

"It’s also important for the public to understand the limitations of technology in protecting humans from extreme heat. In the current reality, technological innovations are often talked about as though they’re the solutions to warming, and this reflects a human tendency to believe that technology can provide miraculous solutions. We must understand that technology isn’t a limitless solution to regulating temperatures. The solutions being proposed, even if implemented, are partial and temporary."

"I like to compare the Earth's rising temperatures to a person coming down with a cold or flu," explains Prof. Price. "When we’re sick, even a half-degree rise in body temperature is significant and affects your symptoms, your mood, and your ability to cope with the illness. The rising global temperatures are like an illness the Earth is experiencing right now, and the symptoms are extreme and changing weather patterns around the world. With every rise in even a fraction of a degree, we’ll see more climate-related natural disasters (floods, wildfires, heatwaves, hurricanes, etc.), and they will become more destructive. The Earth is heating up and has reached new heights in 2024."

"In my view, a major challenge, which we’ve never experienced at this intensity before, is denial," says Prof. Ruth Ronen. "During COVID, the world dealt with a small number of deniers, but on the climate crisis and global warming, denial has become a political trend with a lot of influence. Although climate science is more conclusive than ever, if we don’t deal with the challenge of denial and the politicization of scientific knowledge, science will remain isolated from the public sphere. There’s a paradoxical shift in public awareness of the crisis – on one hand, there’s a wider recognition of the crisis itself (perhaps because reality is hitting us hard). On the other hand, there’s increasing disregard for the meaning of the crisis and the need for drastic measures to stop or contain the warming. This is especially prominent in Israel but certainly also in other places."

Prof. Colin Price, School of Environmental and Earth Sciences, Faculty of Exact Sciences, Tel Aviv University

You both present a difficult picture. Sometimes the discourse around the climate crisis makes it feel like all hope is lost, and maybe there’s nothing to be done, but we’d like to end the article with a positive message, and primarily a call to action. What do you think are the three most important things we need to know or promote on this issue?

"Education, education, and more education," says Prof. Ruth Ronen. "Education should focus on the interaction between humans – from kindergarten children to university students – and the 'life cycle' of industrial products, agricultural crops and natural resources. In what conditions was the tomato in our salad grown? What is the history of industrial agriculture, and how is its growth related to warming? What’s needed for water to flow from the faucet in our kitchen, and how certain can we be that the faucet won’t run dry in the future? How many emissions are 'produced' by every use of the cloud or AI software, and what is the impact on global warming? Through education, we must fight the disconnected and context-less ways in which humans consume and exploit the environment."

"Another important thing in my view is to create a shift in awareness among scientists about their social role at this moment in time," Prof. Ronen continues. "Scientists usually wait to be invited to conferences or informal discussions when there are climate summits or another climate record is broken. They generally don’t manage to convey the urgency of what is at stake. Scientists are used to giving an opinion from the detached point of view of science, but we need scientists who are willing to get actively involved, just like groups of lawyers got involved to explain the implications of the constitutional crisis and judicial reform to the public. This requires a change to take place among scientists, or at least some of them, so that they will be able and willing to engage in public discourse."

"First, we need to change how we use energy," argues Prof. Colin Price. "We consume large amounts of energy for our homes, transportation, industry, etc., and we rely almost entirely on energy from the burning of fossil fuels, which leads to greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere and contributes to the Earth’s heating. We need a change and a shift in the energy sector from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources (solar, wind), synthetic fuels (such as hydrogen), and even nuclear energy. If we want to avoid unnecessary risks, we must complete this transition by 2050, and the longer we wait, the harder it will be. The technologies are already available; the transition depends mainly on political will, not technological capability."

"The second thing is that we need to rethink how we produce food for the 8 billion people on Earth. Agriculture and food production are responsible for significant greenhouse gas emissions, and we need to develop ways to reduce emissions in this sector. One way is transitioning to a diet based on plant proteins instead of animal agriculture (especially reducing cattle farming). A planetary diet shift will be healthier for both us and the planet."

"The final thing we need to understand is that we will never be able to completely zero out our emissions, but we can achieve what's called 'net-zero emissions' – a state where the additional greenhouse gases emitted are offset by those captured back, so the concentration of greenhouse gases does not increase. To achieve this, we need to continue developing technologies and solutions for capturing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere on a significant scale. This requires research and investment to advance these technologies and reduce their costs."

Written by: Judi Lax, Coordinator of the 'Climate Initiative' at Tel Aviv University

If you haven’t joined TAU's Climate Initiative's mailing list to get the newsletter directly to your inbox, please join here.